NOTE: Hank Anderson died June 22 at home in Brewster, Mass. A memorial service was held Sept. 21 in New Milford. Below is our tribute from winter 2018.

Henry B. (Hank) Anderson, a founding partner of Cramer & Anderson who turns 100 on May 30, 2018, reflected on his long, successful, and adventure filled life and career this past winter at the Cape Cod home where he retired with his wife, “Bunny” (Theresa Virginia), in the late 1990s.

The Connecticut Law Tribune Honors Hank Anderson

With a 2018 Lifetime Achievement Award

The son of a dentist from just outside Pittsburgh, Penn., Anderson divides his narrative into three principal story lines—an educational arc taking him to Wesleyan University and later the University of Connecticut School of Law, his Naval service in World War II, when he survived kamikaze attacks on two aircraft carriers, and intertwined roles as small town statesman and an increasingly prominent attorney who played a lead role in shaping the practice of law in Connecticut.

Cramer & Anderson Founding Partner Henry B. (Hank) Anderson at his home on Cape Cod in January 2018.

“All along in the road of life I have happened to be in a particular situation,” Anderson said as the lean afternoon light of January in Brewster, Mass., illuminated his features. “I always fell in with great people who knew what they were doing.”

“You’re just darn lucky,” Bunny observed, to which Anderson replied, “There are a lot of good people left in the world. You’re darn lucky if you happen to find them.”

Attorneys who worked with Anderson, who are enhancing his legacy as they expand Cramer & Anderson and deepen its success, remember fondly a scholar and gentleman with keen intelligence, great instincts, an innate sense of fairness, a passion for words, a taste for world travel, and an informed appreciation of the arts, notably Palladian architecture.

“I want to thank Hank and his generation of attorneys for passing on to us the premier firm in Litchfield County and I hope he feels we have been good stewards,” said Partner Art Weinshank, whom Anderson hired.

“Although already an experienced lawyer when I joined Cramer & Anderson some 21 years ago, I learned something nearly every time Hank and I talked law, either in general or in actual case consults,” said Partner D. Randall DiBella. “He would often raise alternate readings of the case law and legislation relevant to the issue at hand, offer arguments pro and con, and discuss the approach that might be warranted. He’s a terrific academician but has a deft ability to convert theoretical concept to real world problems when the theory is viable and to reject it when it is not. That speaks to great intellectual confidence.”

“Hank is a living example of what Tom Brokaw called ‘The Greatest Generation,” Attorney DiBella added.

Surviving Kamikaze Attacks

Like many Americans, Anderson charted a journey as a young man that was shaped by World War II.

As Anderson was studying for his master’s degree at Wesleyan, the war in Europe intensified. He entered the Navy as a midshipman in June 1941 and was commissioned as an ensign that September, just months before the Dec. 7 attack on Pearl Harbor.

After crash-course training in Chicago (“We went through everything we were supposed to know in three months so we were qualified.”), Anderson joined a squadron of PBY’s, or lumbering reconnaissance planes, in Norfolk, Virginia. He had had some flight training but didn’t credit himself with the skills to be a Navy pilot.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor in December 1941, according to his own biographical account, Anderson was transferred to Naval Air Station Alameda in California, where he served as the enlisted personnel officer of Headquarters Squadron Eight, and then served in the same capacity for Commander Fleet Air, Alameda.

Hank Anderson in his Navy uniform outside Cramer & Anderson’s flagship office in New Milford.

“I became Andy in the Navy,” said Anderson, whose role at Alameda was to meet the crews coming back from fighting and find out what they needed.

“I did that job so well I couldn’t get out of there,” he recalled. “I finally went to the chief of staff and said, ‘This is not fair. I’m not fighting the war.’ He said, ‘You can’t go until you find a replacement.’” So he did.

Toward the end of 1944, Anderson was transferred to the staff of Admiral Marc A. Mitscher, Commander of Task Force 58, the Fifth Fleet’s Fast Carrier Task Force, initially serving as the Awards Officer.

“The Japanese were desperate by 1945,” Anderson recalled. “They couldn’t win. They didn’t want to give up.” So they turned to kamikaze attacks on the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

On May 11, 1945, Anderson survived a kamikaze attack on the USS Bunker Hill, an aircraft carrier, and just days later on May 14, he was aboard another carrier, the USS Enterprise, when it suffered a kamikaze attack.

The remaining members of the staff were transferred to a third carrier, the Randolph, without incident. The flag secretary was killed by a kamikaze attack on May 11 and Anderson took the position.

Arleigh Burke, Chief of Staff to Admiral Mitscher, commended Anderson for organizing firefighting parties aboard the USS Bunker Hill on May 11 and he was awarded a Silver Star. In addition, for services rendered to Admiral Mitscher and his staff as flag secretary, Anderson was awarded a Bronze Star.

“He manned fire hoses and, according to Flag Admiral Arleigh Burke ‘Anderson … fought fires in the hangar deck and gradually, by pure guts and will power, brought them under control … and tended to the horribly wounded aboard the crippled carrier Bunker Hill,’” Attorney DiBella recounted.

“Working for Admiral Burke was one of the best jobs I ever had,” Anderson said. “He wanted everything done right and he wanted it done yesterday, and that was the way I was brought up.”

$10 a Week and the Cases No One Wanted

That philosophy and work ethic carried over into the studies Anderson resumed upon returning to Connecticut, and later defined his long and successful career in the law.

Having returned to Wesleyan to complete his master’s degree, he simultaneously attended the University of Connecticut School of Law in West Hartford, where he was a member of the Connecticut Law Review.

“All the lieutenant commanders in the Navy went to law school, so I said, ‘I’m going to go to law school,’” Anderson recalled.

His Naval service in World War II qualified him for the educational benefits of the new G.I. Bill, adopted in 1944. However, attending two universities at once created a bit of a G.I. Bill wrinkle for Anderson, who remembered, “Nobody pressed me for any payment until I got this straightened out with Washington, D.C.”

Hank Anderson in 2009.

On the same day in June 1948, Anderson received his law degree at UConn in Storrs, and then travelled to Middletown to receive his master’s degree at Wesleyan. It was awarded by his friend and mentor, Victor L. Butterfield, who first recruited Anderson to attend the university while serving as Director of Admissions and rose to become president of Wesleyan.

The next challenge for Anderson was finding work as a young attorney.

“There wasn’t any attorney in New Milford who had enough work to be in a position to take on a subordinate,” Anderson recalled. “Harry Bradbury said, ‘Pay me $10 a week and you can have any office,’ and that’s how I started.”

Bradbury, a New Milford attorney, was a fellow Wesleyan graduate. Anderson worked with him—getting “all the cases nobody wanted”—through the fall of 1950, when he was asked to join forces with Attorney Francis S. Ferriss, forming the firm Ferriss and Anderson.

Attorney Ferriss died suddenly in 1957, at which point Anderson asked his friend Paul B. Altermatt to return from Indiana to his hometown of New Milford, which led to the formation of Anderson and Altermatt.

On Jan. 1, 1962, Attorneys Anderson and Altermatt merged with the firm of Cramer, Blick, Fitzgerald and Hume, which had offices in Litchfield and New Milford, to form Cramer & Anderson. It would be Anderson’s home for nearly four decades until he retired from the firm on Dec. 31, 1998.

In terms of his own practice, Anderson focused on Real Estate Law, estates, and municipal work. “We had people who litigated. I was not a good litigant,” he recalled.

‘Brilliant Ability And Genuine Compassion’

“During his fifty years of law practice in the New Milford area Anderson was heavily active in the legal community,” a UConn Law Alumni Spotlight story says in recounting Anderson’s many important accomplishments. “He was a founder of the Connecticut Attorneys Title Insurance Company and served as a director on the executive committee. He also served on the Connecticut Bar Examining committee in multiple capacities—member, secretary, and eventually chairman. He was president of the Litchfield County Bar Association, Chairman of the real property section of the state bar, and served as director of Connecticut Legal Services in Middletown.”

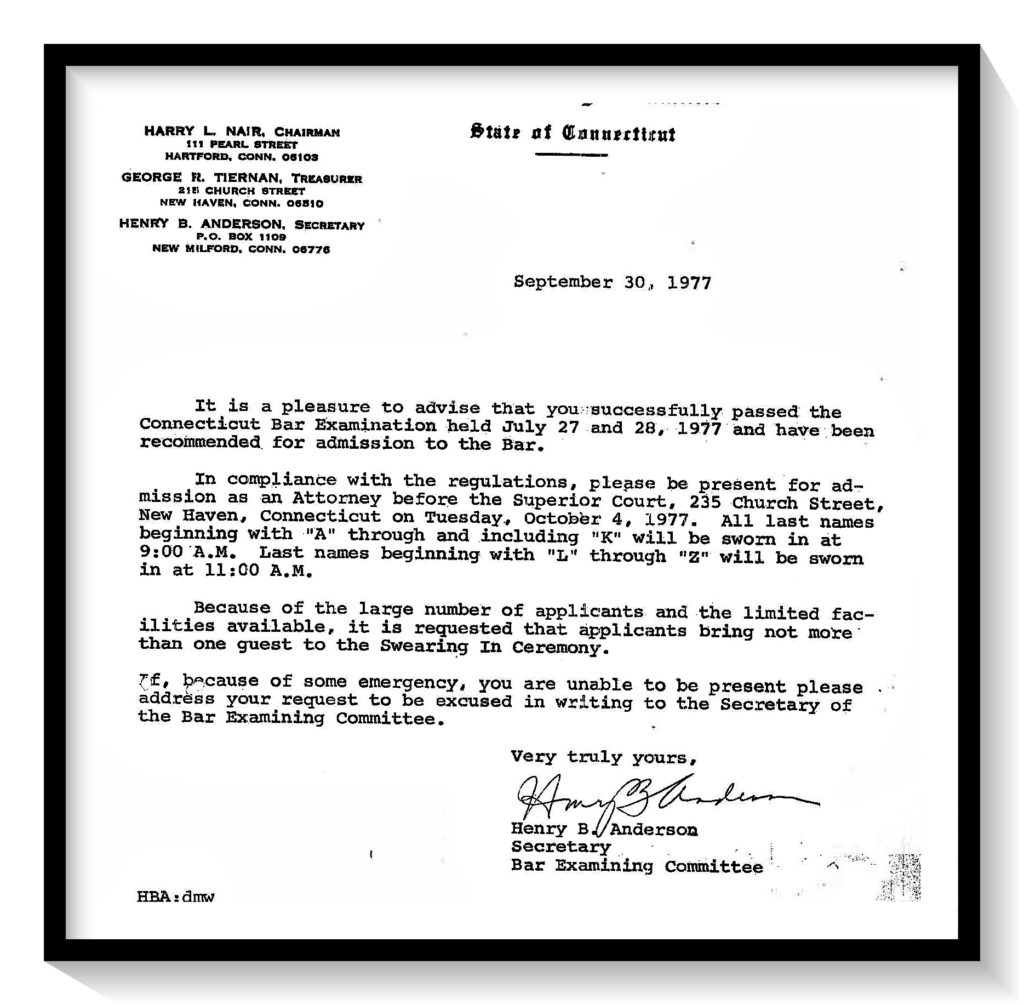

Cramer & Anderson Partner Kim Nolan remembers well Anderson’s role as secretary of the Bar Examining Committee. “Back in 1977, I, along with others who had taken the bar exam that July, eagerly awaited the  results,” Attorney Nolan recalled. “In 1977 there were of course no online results, just an old fashioned letter in the mail!”

results,” Attorney Nolan recalled. “In 1977 there were of course no online results, just an old fashioned letter in the mail!”

When the letter arrived announcing that Attorney Nolan had passed the Connecticut Bar Exam, it was signed by Hank Anderson. “I kept the letter all these years as a reminder of what was for me a major milestone of getting by the exam and being admitted to the Connecticut Bar,” Attorney Nolan said. “Then, when I joined the firm bearing Hank’s name, the letter took on added meaning and I now proudly display the letter in my office.”

Anderson also served on a Real Property Committee of the National Conference of Bar Examiners from 1974 to 1985, drafting real estate questions for bar examining committees throughout the nation. He was a lecturer on real estate law for the Connecticut Board of Realtors, and chairman of the Real Property Section of the Connecticut Bar Association.

In addition to serving as president of the Litchfield County Bar Association, Anderson was a Fellow of the Connecticut Bar Association and Fellow of the American Bar Association.

He served for a decade on the Grievance Committee for Litchfield County, and Gov. Lowell P. Weicker, Jr. appointed Anderson a member of a statutory group that supervised distribution of funds by legal service organizations in Connecticut.

He was so busy contributing in so many roles, Anderson recalled, “At one time I had four secretaries, including ones for real estate and estate work,” Later he elaborated, “None of what I accomplished as a member of the Bar could have happened without good, loyal secretaries, and paralegals. I never went to court without the right file.”

While Anderson lived in several Connecticut towns, including Warren, Southbury, and Old Saybrook on the shoreline, it was Sherman, where he lived for many years, that was most indelibly his home.

“In 1949 they decided to have a town counsel in Sherman with pay of $100 a year,” Anderson recalled while looking back on his career that winter’s day on Cape Cod. Not only did he serve as town counsel for about 20 years, but Anderson was also elected to be the moderator of the town meeting, the equivalent to a legislative body for important matters of town government.

“I was elected every time to the job. I thought I made enough enemies I would get thrown out, but they never turned me down,” he said, remembering the time he had to eject a resident who had too much to drink, or when he had to cut off another resident who was attempting to speak again and again.

In Sherman, Anderson, who served on the Executive Committee of the Connecticut Probate Assembly, was also Judge of Probate. As a trial justice he presided over the local Justice of the Peace court.

“In addition to his military accolades, Anderson was the recipient of numerous distinguished legal awards,” the UConn Law story says. “In 1989 he was voted Citizen of the Year by the State of Connecticut Courts of Probate. In 1990 The Connecticut Bar Association awarded him the John Eldred Shields Award for his professional services to the community at large—over 900 hours of pro bono services. He was also voted Probate Attorney of the Year by the Connecticut Probate Assembly.”

“No matter the demands upon him during the 42 years of his distinguished career, Henry B. Anderson has always made time to serve his profession and his community with brilliant ability and genuine compassion,” the Shields Award citation said.

The more than 900 hours of pro bono services cited in the Shields Award came from Anderson’s work on a difficult case. After Attorney and Danbury Judge of Probate Richard L. Nahley committed suicide on Nov. 20, 1987, Anderson was appointed a co-fiduciary of his last will and testament. Claims against Nahley’s estate exceeded $3 million, and for Anderson settling the estate involved disposition of lawsuits in the Danbury probate court, various superior courts, and the federal courts. All the complicated claims were eventually settled, and Anderson made sure every legitimate claim was paid in full. For his distinguished professional services, in addition to the Shields Award, the Connecticut Probate Assembly voted Anderson Probate Attorney of the Year.

Renaissance Man

At Wesleyan University, Anderson had majored in mathematics and minored in classics, and in addition to compiling what Attorney Nolan described as an “illustrious career” in the law, Anderson was also a scholar and connoisseur of travel, history, languages, and the arts.

He loved swing music, the jazz era and the big bands of Benny Goodman, the Dorsey brothers and others. (In 1936 he was voted the best dancer in his senior high school class.) In college he also developed an affection for comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan.

Anderson was fascinated by ancient civilizations and took numerous courses in Latin and Greek, visiting Greece, its Archipelago, and Italy, among other travels.

A self-taught linguist and amateur etymologist, Anderson amassed a library of dictionaries and atlases, extending from English to Latin, ancient and modem Greek, French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese. The dictionaries were everywhere; his office, in the car, in his travel back and all over the house.

When his children were young, Anderson purchased land in New Fairfield on Candlewood Lake, where his family and friends enjoyed boating, swimming, camping, fishing and water skiing.

Later, in his 40s and 50s, Anderson enjoyed downhill skiing with Attorney Altermatt and Kenneth F. Grant, the first selectman of Sherman. “Many a weekend in winter was spent in Vermont, usually skiing Mad River Glen. Anderson skied with little finesse but always reached the base without incident,” his bio recounts. “He and Ken Grant were know as ‘Los Toros De Las Montanas.’”

“Hank had (and still has) many interests, especially history,” said Partner Robert L. Fisher, Jr. “For a period of time he was very interested in Palladian windows, so he researched everything he could find. A Palladian window is a specific design, a large, three-section window where the center section is arched and larger than the two side sections. Renaissance architecture and other buildings in classical styles often have Palladian windows.”

It was continuing education studies in the history of art after his family was grown that led to Anderson’s interest in Palladian architecture, and Cramer & Anderson’s flagship office in New Milford has an excellent Palladian façade. The office is located in a historic 1793 structure built as the home of successful merchant, real estate investor and U.S. Senator Elijah Boardman, and is famously the subject of a circa 1796 painting by Ralph Earl owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Anderson assembled slides of Palladian architecture in Danbury and across Litchfield county, and in 1984 he joined a Pratt Institute educational trip to Italy to study Palladian architecture in Vicenza, Padua, Venice and other cities. Anderson came back with excellent slides of Palladio’s masterpieces in northern Italy and gave occasional lectures to audiences in Connecticut.

“Hank is still a history buff,” Attorney Fisher said. “When I spoke with him a few months ago, I asked him how he was doing. He responded that he intends to make it to 100, but then qualified that comment by saying he no longer remembers much about the Peloponnesian Wars.”

Anderson was also an avid gardener, and the four acres where he once lived Warren were known as “Casa Galatea.” Over 17 years, he dug a pond, installed a sandy beach, and guided the overflow into a stream. Anderson created paths through the woods, and embellished the signature shadbush and dogwoods with perennials of all kinds. He was a member of the “Mad Gardeners” and his gardens were on group’s tour for several years.

When he and Bunny moved to Cape Cod on April 15, 1999, they built a new Timberpeg home on a raw lot. They visited every nursery within 30 miles for special plants, and by June of 2002 they had developed an excellent perennial garden, including 20 varieties of dogwood.

Hank Anderson often quoted Ovid, who said, “May death find me at my work,” and Montaigne who said, “Je veux que la mort me trouve plantant mis chous,” which translates as “I hope that death finds me planting my cabbages.”

~